Characterizing unknown unknowns

Abstract

Unidentified risks, also known as unknown unknowns, have traditionally been outside the scope of project risk management. Most unknown unknowns are believed to be impossible to find or imagine in advance. But this study reveals that many of them were not truly unidentifiable. This study develops and suggests a model to characterize risks, especially unidentified ones. Through the characterization of unknown unknowns, the model helps identify what had been believed to be unidentifiable or unimaginable risks. Finding more unknown unknowns means converting them to known unknowns so that they become manageable using project risk management. This model is designed to help project managers identify hidden risks, but it is customizable to serve anyone who copes with risks.

Introduction

Disasters like Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010, and the Fukushima nuclear accident in 2011 were unanticipated yet extremely damaging. It might seem that such disasters could not have been expected or imagined and therefore not preventable. Indeed, some risks are impossible to detect or even imagine in advance. Checklists or risk breakdown structures of similar projects can help project managers find typical risks but won’t help much for such unprecedented events.

Many people have been trying to understand the nature of hard-to-detect risks or uncertainties. After former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Henry Rumsfeld mentioned “unknown unknowns” (Rumsfeld, 2002), people started using quadrants of knowledge, i.e., known known, known unknown, unknown known, and unknown unknown, to understand and explain the nature of risk. Project managers try to maximize known knowns by detecting as many unknown knowns as possible, as early as possible. However, it is impossible to identify all risks in advance for many reasons (Hillson, 2005), and unidentified risks remain as unknown unknowns until they are identified or actually happen.

Much research has explored how to better understand unknown unknowns. The challenges usually reside in the nature of unknown unknowns but, sometimes, problem exists in people rather than the event itself. The major obstacle to addressing unknown unknowns is their being hard to imagine, but another is that people who cannot cope with unknown unknowns will sometimes actively ignore them (Alles, 2009). Although unknown unknowns may be unidentifiable, they might be presumed likely in some component of the project. Diagnosing gaps in the knowledge about certain subproblem areas can predict the presence of unknown unknowns but cannot identify them (Loch, Solt, & Bailey, 2007). A likely event cannot be thought to be unknown unknown because it is already identified, but its consequence may fall into the category of unknown unknowns. The occurrence of an event like a natural disaster may be forecasted easily, but its impact is not easy to predict or estimate because of knock-on effects (Ogaard, 2009).

Despite that project risk management acts as“forward-looking radar,” it is not possible to identify all risks in advance, in part for the following reasons (Hillson, 2005):

- Some risks are inherently unknowable.

- Some risks are time-dependent.

- Some risks are progress-dependent.

- Some risks are response-dependent, i.e., secondary risks.

Uncertainties may be categorized other than as known unknowns or unknown unknowns. One scheme classifies uncertainty as either subway uncertainty or coconut uncertainty (Makridakis, Hogarth, & Gaba, 2009). Subway uncertainty refers to what can be modeled and reasonably incorporated in probabilistic predictions that assume, for example, normally distributed forecasting errors. Coconut uncertainty pertains to events that cannot be modeled, and also to rare and unique events that are simply hard to envision. To put it simply, subway uncertainty is quantifiable and coconut uncertainty is not. Another way to categorize uncertainties is by whether knowledge and information about them exists but is not accessible, or simply does not exist. The impact of uncertainties of the latter type cannot be evaluated in advance (Stoelsnesa, 2007).

A more detailed way to categorize uncertainties is based on the source of uncertainty (Ward & Chapman, 2003), i.e., variability associated with estimates, uncertainty about the basis of estimates, design and logistics, objectives and priorities, and fundamental relationships between project parties. Each category has subcategories, and this categorization is very project-specific and varies by project.

A typical classification of risks is based on the level of knowledge about a risk event’s occurrence (either known or unknown) and the level of knowledge about its impact (either known or unknown). This leads to four possibilities (Cleden, 2009):

- Known–knowns (knowledge),

- Unknown–knowns (impact is unknown but existence is known, i.e., untapped knowledge),

- Known–unknowns (risks), and

- Unknown–unknowns (unfathomable uncertainty).

The proposed model modifies and extends these categories to incorporate insights from the literature. This is discussed in the next section, which also explains how to use the model to identify hidden uncertainties and shows how recent catastrophes can be mapped to the model. The final section concludes.

Model to Characterize Unknown Unknowns

Modifying Typical Risk Classification

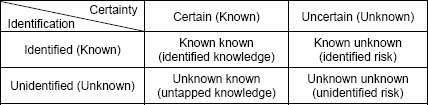

The development of the model starts with the quadrant model described in the previous section. This classification gives an insightful framework to view various risks but “occurrence” and “impact” doesn’t clearly distinguish identity from occurrence. Suppose there is a very rare but well-known event. People know its identity but don’t know if it will really happen. According to Cleden (2009), this event should be classified as unknown unknown because the occurrence is uncertain and the impact is also uncertain. Suppose there is an event with unintended consequences. “Unintended consequences” is the matter of identification not the matter of uncertainty of occurrence or impact. According to Cleden (2009), this event can be classified as any one of the four possibilities depending on the uncertainty of occurrence and the uncertainty of the magnitude of the identified impact. This classification assumes that every risk event is already identified, but it doesn’t help characterize unidentified risks. In order to distinguish identified risks from unidentified risks, the “level of knowledge about the risk occurrence” should be about being able to identify the risk in advance or not. So, the proposed model labels it “identification.” The “level of knowledge about the impact” should include occurrence as well as impact since either occurrence or impact of a risk can be uncertain. So, the model labels it “certainty.” Exhibit 1 shows a schematic structure of the risk categorization. In this table, the model categorizes events by “identification” and “certainty.”

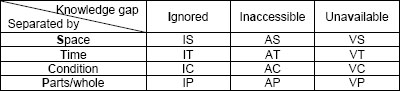

Exhibit 1: Schematic Structure of Modified Risk Categorization

In this matrix, if the nature of an event is certain, it is more like a fact or knowledge. It could be what we already know, i.e., known known, or what we don’t know yet, i.e., unknown known. If the nature of an event is uncertain, the occurrence can be uncertain, i.e., probability of occurrence is less than 1, and the impact can be uncertain as well. For example, a hurricane has two basic uncertainties. One is track, represented by the chance of landfall, and the other one is intensity, represented by wind speed or hurricane category. If either one of occurrence or impact is uncertain, that event is considered to be uncertain. Often times, people know the identity of an uncertain event, which means known unknown. Sometimes, people even don’t know what that is, which means unknown unknown. Most natural disasters are uncertain events but people already know what they are.

In this matrix, known unknowns usually are treated as “risks” in project risk management (PRM) as defined in A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge Guide (PMBOK® Guide) (Project Management Institute, 2008). On the other hand, unknown unknowns are considered to be unfathomable or even unimaginable to many people and PRM does not attempt to account for unknown unknowns.

Once identified, an unknown unknown is converted to a known unknown and moved to the quadrant at the right top in this matrix. Converting unknown unknowns to known unknowns means reducing the number of unidentified uncertainties even though we don’t know how many of them are still remaining unidentified. The more unknown unknowns are identified, the less chance a project will have to be affected by a surprise.

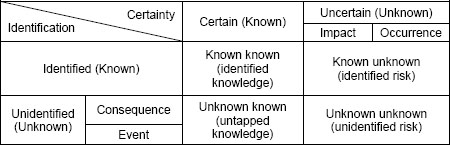

Extensions of the Modified Risk Categories

The study found that all unknown unknowns are not same and significant portion of them are not truly unimaginable. Unknown unknowns in Exhibit 1 can be interpreted as “unidentified uncertain event.” “Uncertain event” is not as simple as it may look. The occurrence of an event can be uncertain as represented by a probability. The impact of the event can also be uncertain as represented by a probability distribution.

“Unidentified” events are not as simple as they may look. The identity of an event can be unidentified but its consequences can also be unidentified, especially when an event has multiple consequences. For example, natural disaster like Hurricane Katrina was an event already identified but many of its consequences were not identified before they really happened. Unidentified consequence is different from estimation error. Estimation error is overestimation or underestimation of the magnitude of a consequence but unidentified consequence is about unintended effects of an event that are different type from identified consequences.

Classifications of the unidentified and the uncertain explained above extends Exhibit 1 as shown in Exhibit 2.

Exhibit 2: Extension of Unknowns

All “unidentified” events are not the same in terms of knowledge gap. Some of them are not identified because there is no access to the knowledge or information even though they are available (Stoelsnesa, 2007). Some of them are unimaginable because the knowledge or information is not available. Some of them have already been detected but are neglected for some reason.

An unidentified risk may be identified under a special circumstance. A person or a group of people may have identified a risk that is not identified by most people. This risk is an unknown unknown to most people, but is a known unknown to that person or group. A risk that is not identified today may have been identified in the past. A risk that is not identified under normal condition may be identified under some condition like political or climatic condition. A risk that is not identified at a project level may be identified at a component level or a higher level.

Risks that are not identified separately may be identified when combined or interacting with each other in forms of new risks or unintended consequences.

To include different categories of “unidentified” described above, the model extends each “unidentified” quadrant in Exhibit 1, i.e. unknown known and unknown unknown, as shown in Exhibit 2. “Unidentified” is classified in two ways: (1) the type of knowledge gap; and (2) how the identification is separated. The model includes three types of knowledge gap. One type labeled “unavailable” means that there is no knowledge or information to access in advance. In this case, the risk is unimaginable. Another type labeled “inaccessible” means that the knowledge or information is available but people have no access to it. The last type labeled “ignored” means that the knowledge or information was already detected but is ignored or neglected for some reason.

Exhibit 3: Classifying “Unidentified”

The other way to classify “unidentified” is by how the identification is separated. This model adopted separation principles of TRIZ (Savransky, 2000) to classify “unidentified” based on how the identification is separated. There are four basic separation principles and first one of them is separation by space labeled “space” in Exhibit 2. This means that a risk can be identified or not depending on physical space, geographical region, professional discipline, or individual. A knowledge or risk that is not identified in most places may be identified only in a region. A knowledge or risk that is not identified by most people may have been identified by an individual or a group of people. Second, one is separation by time labeled “time” in the table. This means that a risk can be identified or not depending on the timing. An event that is not identified right now may be identified at a specific point of time in a project. Some risks are time-dependent or progress-dependent and can be identified only at some point of time or phase in the project. Third, one is separation by condition labeled “condition” in the table. This means that a risk can be identified or not depending on conditions. The condition can be political condition, environmental condition, physical condition, or previous actions taken. Some risks are response-dependent, i.e., secondary risks, and they are conditioned to a specific response. The last one of them is separation by parts/whole labeled “parts/whole” in the table. This means that a risk can be identified or not depending on the scale. Some risks can be identified only at subsystem level, like components of a system or project. Some other risks can be identified only at super system level, like project, program, or enterprise. Some risks can be identified only in combination or interaction of multiple risks. Items in known knowns and known unknowns quadrants may feed into this category.

In this table, a project can be investigated in 12 different combinations and it means that there are 12 different ways to identify unknown knowns or unknown unknowns. For example, instead of just trying to find any hidden risks in a project, a project manager can seek for hidden risks asking questions like “What can be a risk neglected by people?”, “What can be a risk that happens in a certain condition?”, or “What can be an “inaccessible” risk that happens when interacting with other events?”

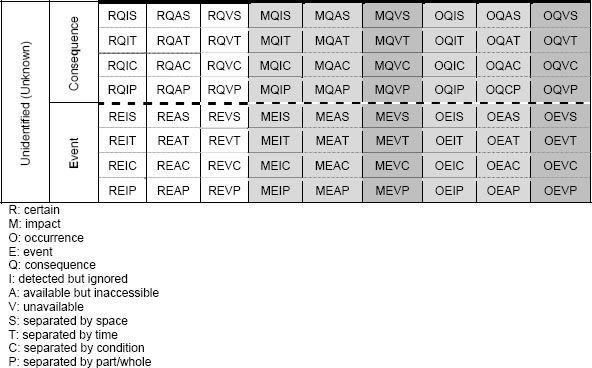

After considering all the perspectives described previously, a basic model is shown in Exhibit 4. Unknown unknowns now have 48 subcategories.

Exhibit 4: Extended Model for Characterizing and Identifying Unknown Unknowns

Shaded areas in the table indicate unknown unknowns. Darker shade areas indicate true unknown unknowns because there is no knowledge available in advance. Roughly speaking, lower cells are harder to identify than higher cells and right cells are more uncertain than left cells. We need to know known knowns and known unknowns to start with. They can be seeds to identify the unidentified. Next, we should check larger categories like impact and occurrence under “uncertain” and event and consequence under “unidentified” for any hidden risks. And then, we should check types of knowledge gap and separation. Finally, we should check each cell.

Converting uncertain events to certain ones would be scientists’ job but converting unidentified risks to identified ones would be project managers’ duty. Identifying as many “unidentified risks” as possible so that they are transferred to known unknown quadrant and only minimal number of “unidentified risks” still remains unidentified is the goal of my model.

Case Studies

Hurricane Katrina in 2005 is the costliest natural disaster and one of the five deadliest hurricanes in the history of the United States (Knabb, Rhome, & Brown, 2005). It was not just one of many hurricanes nor force majeure. In hindsight, it was revealed that this natural disaster had unidentified risks, i.e., unknown unknowns. Category 3 hurricanes combined with the failure of the region’s flood-control system and the problem with the design of the levee structure created unexpectedly high loss.

In the proposed model, the event was not unidentified but the consequence was unidentified. The risk was detected and but neglected. The unexpected consequence from the combined risks was not identified. Both of the occurrence of the hurricane landfall and its impact were uncertain. So, what used to be unknown unknowns about Hurricane Katrina can be mapped to MQIS, MIQP, OQIS, and OQIP in Exhibit 3, none of which is in the shaded area. Of course, they are no longer unknown unknowns since they are identified because of what happened in New Orleans in 2005.

Deepwater Horizon BP Oil Spill in 2010 is the largest accidental marine oil spill in the history of the petroleum industry (Robertson & Krauss, 2010). Some people might think the risk was technical and it happened unexpectedly due to the technical challenges in extreme environment. But, in hindsight, it was revealed that there was “a rush to completion” on the well and the management made poor decisions despite several indications of potential hazard. So, the oil spill was the result of the combination of technical risk and managerial risk. The oil spill risk was not unidentified but possible consequences were not properly identified, partly because of the extreme condition, or the risk was neglected for some reason. Both occurrence and impact magnitude of the oil spill were uncertain. So, what used to be unknown unknowns about Deepwater Horizon BP oil spill can be mapped to MQIS, MQIC, MIQP, OQIS, and OQIP in Exhibit 3. None of them is in the shaded area and it indicates that there was no true unknown unknown even thought this disaster was a big surprise to most people.

Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011 is the largest nuclear disaster since the Chernobyl disaster of 1986 (International Business Times, 2011). The disaster was initiated by the large earthquake with a 9.0 magnitude and the large tsunamis with 30-46 feet high waves (Perrow, 2011). Considering the magnitude of the natural disasters, some people might think the disaster was force majeure and there was nothing they could do about it. But, in hindsight, it was combination of natural disasters, technical risks, plan & communication problems, and cultural issues. The risk was identified but the warnings were ignored. The risk event was identified but the consequences were not properly identified. Both the occurrence and the impact were uncertain. So, what used to be unknown unknowns about Fukushima nuclear disaster can be mapped to MQIS, MQIC, MIQP, OQIS, OQIC, and OQIP in Exhibit 3. Just like previous cases, none of them is in the shaded area and it indicates that there was no true unknown unknown even thought this disaster was a big surprise to most people.

Conclusion

Recent surprises that caused catastrophic losses raised the needs for any method to expect the unexpected and identify them in advance. Finding common and typical risks would be relatively easy with the help from conventional tools but identifying non-typical risks in advance has been believed to be very difficult. Based on insightful findings from literatures and recent catastrophes, a matrix model to help identify the unknown unknowns in advance has been developed. This model does not provide comprehensive list of unknown unknowns but it will contribute to reducing the surprises that could have been identified and prepared before they happen.

This model will help project managers but it is still necessary for them to repeat the use of the model on a regular basis to identify hidden risks because some risks are still not knowable in advance.

This model is designed for project managers dealing with risks but it is general enough to be tailored or extended for various projects or disciplines. The model can have more categories or new dimension when necessary.

Future research will include testing, validating, and enhancing this model in real projects.

References

Alles, M. (2009). Governance in the age of unknown unknowns. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 6, 85–88.

Cleden, D. (2009). Managing project uncertainty. Farnham, UK: Gower.

Hillson, D. (2005). Why Risks Turn into Surprises, Risk Doctor Briefings [Electronic Version] No.16. Retrieved from http://www.risk-doctor.com/pdf-briefings/risk-doctor16e.pdf

International Business Times (2011, April). Analysis: A month on, Japan nuclear crisis still scarring. International Business Times [Electronic Version] Published on April 9, 2011. Retrieved from http://www.ibtimes.co.in/articles/132391/20110409/japan-nuclear-crisis-radiation.htm

Knabb, R. D., Rhome, J. R., & Brown, D. P. (2005). Tropical cyclone report: Hurricane Katrina: 23-30 August 2005, National Hurricane Center [Electronic Version] Last updated September 14, 2011 Retrieved from http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/TCR-AL122005_Katrina.pdf

Loch, C. H., Solt, M. E., & Bailey, E. M. (2007). Diagnosing unforeseeable uncertainty in a new venture. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 25, 28–46.

Makridakis, S., Hogarth, R. M., & Gaba, A. (2009). Forecasting and uncertainty in the economic and business world. International Journal of Forecasting, 25, 794–812.

Ogaard, R. (2009, March). Known unknowns. Reinsurance, p. 9.

Perrow, C. (2011). Fukushima, risk, and probability: Expect the unexpected. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists [Electronic Version] Retrieved on August 8, 2012 from http://thebulletin.org/web-edition/features/fukushima-risk-and-probability-expect-the-unexpected.

Project Management Institute. (2008). A guide to the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK® guide) (4th ed.). Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

Robertson, C., & Krauss, C. (2010). Gulf spill is the largest of its kin, scientists say, The New York Times, [Electronic Version] Published August 2, 2010. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/03/us/03spill.html?_r=2&fta=y

Rumsfeld, D. (2002). Department of Defense news briefing, February 12, 2002. Retrieved on August 8, 2012 from http://www.defense.gov/Transcripts/Transcript.aspx?TranscriptID=2636

Stoelsnesa, R. R. (2007). Managing unknowns in projects. Risk Management, 9(4), 271–280.

Savransky, S. D. (2000). Engineering of creativity: Introduction to TRIZ methodology of inventive problem solving. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Ward, S., & Chapman, C. (2003). Transforming project risk management into project uncertainty management. International Journal of Project Management, 21(2), 97–105.

© 2012, Seong Dae Kim

Originally published as a part of 2012 PMI Global Congress Proceedings – Vancouver, British Columbia

Original document,Characterizing unknown unknowns

Source:PMI

Adapted for Academy.Warriorrising